Origins of Indonesia Batik

Batik’s roots are most commonly traced to the Indonesian island of Java. Many argue that this is where the art of batik design has and continues to be developed to its highest standard, utilising raw materials for the wax and dye, including deep blue hues obtained from the plant of indigo, which conveniently grows in abundance on the island. Other readily available resources utilised in the batik process include cotton and beeswax, as well as yellow and browns from tree barks, heartwood and roots.

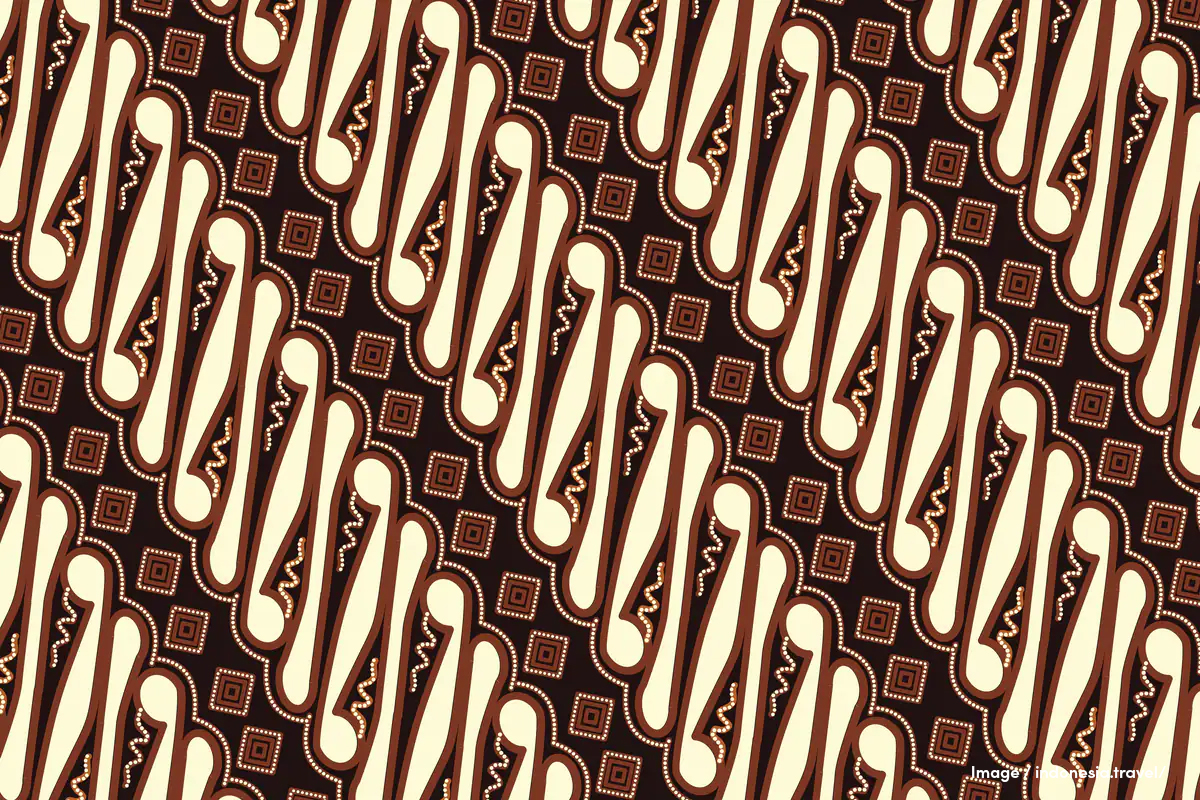

The traditional batik patterns and colours are most commonly applied in Central Java, where original practices and techniques are most closely adhered to—blue, brown, beige and black are the most common traditional colours, derived from the natural environment. The earliest application of batik fabrics was for personal and ceremonial purposes. It is believed that batik was once a tradition that could only be practised in the palace, reserved for the clothes of the king, family and royal followers. It is only in the north coast of Java, near Pekalongan and Cirebon, where more modern and vibrant colours and designs became more prevalent.

Whilst resist-dyeing techniques have been around for centuries, within many Asian cultures, its prominence and artistic expression reached its peak in Indonesia in the 19th and 20th centuries.